April 2024 Decorative Arts

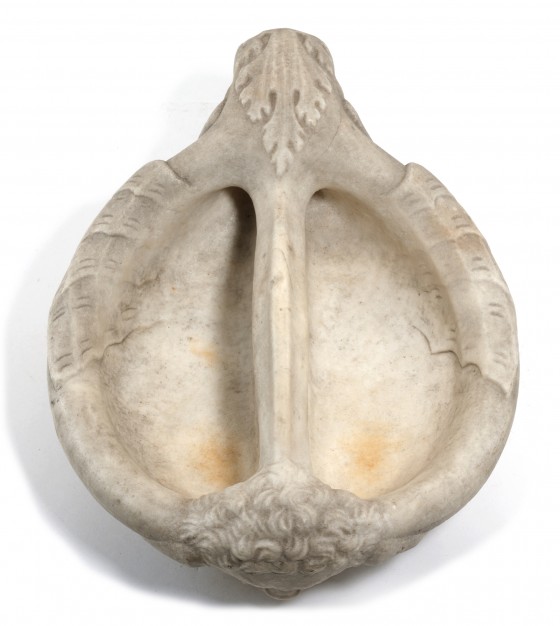

Lavamano with diabolic motifs

An object with rich symbolic connotations, this lavamano, made in Tuscany in the early 16th century depicts a complex, fantastical bestiary, drawing on ancient and Gothic references. The monster shown is like the infernal creatures believed to populate the entrails of the Earth, according to Western imagination at the time. Up until 22 July 2024, this lavamano with diabolic motifs can be found temporarily at the Musée du Louvre-Lens as part of the Underground Worlds exhibition.

See the artwork in the collectionLavamano with diabolic motifs Circa 1505-1520

Tuscany

White marble

16 x 26.5 x 34 cm

FGA-AD-OBJ-0023

Fondation Gandur pour l’Art, Genève

Provenance

Marc-Arthur Kohn, Paris, 18 March 2011, lot no. 39

Skilfully combining decorative and utilitarian functions, this small, sculpted marble basin boasts a rather surprising and original form, along with an ornamental hybridity. The basin has a circular form and takes on the appearance of a monstrous two-headed creature, born from the assembly of elements themselves coming from various iconographic spheres. Resting both on the two front legs of the monster, equipped with clawed feet, and on one of its mouths, the basin also features a curved handle in the shape of a dorsal spine, allowing it to be held easily.1

A dragon…?

The front of the basin bears a dragon-like figure, whose mouth, sculpted in the round, acts as an outlet for the water, which flows through the impressive half-open jaws with hostile fangs (ill. 2). The creature’s pointed ears and small beard allow the figure to be easily identified as belonging to the realm of fantastical religious bestiary. This identification is reinforced by the organic extension of the body into ribbed wings appearing in bas-relief on the sides of the basin (ill. 3), along with the handle evoking the dragon’s legendary “spiked back”.2

In the early 16th century, the hybrid figure of the dragon had already existed for a long time, drawing its origins from Sumerian culture, in the form of a winged monster with a serpent’s head, which gradually blended with the serpent from the Tree of Life in the Bible, considered to be at the root of the original sin.3

A symbol of evil, the dragon also appears in the Bible in the guise of the seven-headed beast of the Apocalypse. If the Romanesque capitals of Moissac represent the devil as a simple snake without wings or legs,4 Gothic art gradually developed an ensemble of characteristics that became emblematic: scales, a crest (here, rather unusually evoked by a kind of stylized acanthus leaf), and above all, equipped with membranous, bat-like wings.

Appearing from the 13th century onwards in illuminated manuscripts, these wings may originate from Chinese representations of evil demons.5 The ribbed or veined appearance of the wings helps to distinguish them from those of angels, usually depicted with feathers. From a symbolic point of view, this choice can also be explained through the association of bats with the shadowy realm of Evil.6 A fallen angel, Satan exchanged his celestial wings for those of the blood-sucking nocturnal “rat-bird”.

As the incarnation of diabolical forces, the dragon was frequently featured in the stories of the Golden Legend, depicting the struggle between Good and Evil, or rather, the triumph of the former over the latter. The dragon, for example, was slain by Saint George, who stabbed the monster with his sword in order to free the Princess of Trebizond (ill. 4), or defeated by Saint Marguerite, who managed to miraculously escape from the creature’s stomach, thanks to the cross she held in her hands (ill. 5). The iconography of this lavamano makes use of this Gothic art cliché, by means of the handle, inviting one to hold and therefore, to dominate the monster.

or…satyr…?

At the back of the basin, another head appears in place of the dragon’s posterior, which refers to another creature, itself a hybrid, and too endowed with diabolic connotations. With a large, unkempt beard, a flat nose, and small goat-like ears, this face, sculpted in simple relief (ill. 6), is undeniably that of a satyr, a creature half-man half-goat taken from Greco-Roman mythology (ill. 8). Associated with a wild or savage form of life found in woods, this creature was also known for its unbridled sexuality, alluded to here by means of the phallic shape protruding from the satyr’s chin underneath the basin (ill. 7).

The antique satyr thus constitutes one of the main sources of traditional diabolic iconography:7 on the margins of civilization, and therefore, by extension, of the divine order, he was seen as a natural demon, often mentioned in accounts by anchorites or hermits and the Desert Fathers.8

This creature experienced a revival of interest during the Renaissance in connection with the rediscovery of ancient Greece and Rome, giving rise to a profusion of depictions, notably small sculptures,9 as evidenced with this small bronze belonging to the collections of the Fondation Gandur pour l’Art, made in Northern Italy after 1550 (ill. 9). Intended for an erudite humanist public, this statuette served to celebrate a “joyful paganism, which allowed one to dream about that which the Christian world rendered unthinkable and diabolical”.10

…or gryll?

Although located at opposing ends of the basin, the figures of the dragon and the satyr are organically linked by the presence of serpent-like tentacles that coil under the basin, giving birth to an even more monstrous creature, and even more diabolical. Through its composite character, the fantastical being shown on thelavamano is similar to the motif of the Gothic gryll.

With its playful dimension, the gryll constitutes one of the distinctive marks of the imaginative infernal repertoire used in Nordic painting in the late Middle Ages, particularly by Hieronymus Bosch and his followers, like Jan Mandyn or Pieter Huys. The Fondation Gandur pour l’Art has an eloquent representation of the latter’s Christ before the Gates of Hell (ill. 10).

Whereas the dragon evokes the darkness of Evil, notably through the bat-like wings, and the satyr a form of natural chaos opposing the divine order, the significance of the gryll, in its explicitly monstrous dimension, is dually diabolic. Its hybrid and composite assemblage appears to be the prerogative of the devil in opposition to the divine order: it manifests the “negation of the order that divine creation inserted into chaos in order to make a cosmos”.11 The ugliness implied by this hybridity is in itself an image of Evil, according to a process of demonization resulting from the dogma of transubstantiation emerging after 1215 and becoming increasingly accepted towards the late Middle Ages.12 In this sense, the creature formed by the lavamano evokes the infernal universe in various ways, along with its monstrous creatures believed to embody the forces of evil. If the dragon specifically is linked to the four elements, the satyr, in its forest dimension, refers more to the earth. However, it is the merging of these two creatures into a new monstrous being that affiliates the latter with an infernal realm located deep in the entrails of the earth.13

A purifying function

How are we to understand the use of such a diabolic iconography on an object otherwise visibly assigned to a hygienic function? In all likelihood, this object seems to have been intended to receive water, and specifically to pour it: moreover, only the gesture consisting of tipping the basin forwards to allow the water to flow out from the dragon’s mouth allows users to perceive the complexity of the satyr’s face and appendages. Like metal aquamaniles, this object may therefore be linked to a practice of hand washing, either in a religious context, in the refectory of a convent for example, or in a domestic context, i.e., in the home of a wealthy individual. From a symbolic perspective, the washing of hands serves as a metaphor for the purification of the soul sought by believers. In this regard, the diabolic bestiary presented on the lavamano constitutes an implicit allusion to the eradication of these infernal forces through purification. Its presence on an object potentially intended for private use reflects the growing place held by the conception of hell in the construction of individual consciousness in the late Middle Ages.14

A typically Florentine work

In terms of the composition and iconography, the lavamano can be considered a miniature evocation of the washbasin sculpted by Andrea del Verrocchio and Antonio Rossellino circa 1460-1470 in the former sacristy of the San Lorenzo Church in Florence (ill. 11).15 Intended to be used by priests to wash their hands before mass, the latter also bears decorative motifs featuring a confrontation of hybrid monsters with dragon bodies and women’s heads. This parallelism helps to place the object in the Florentine context of the early 16th century, as do the archaic references to the Gothic universe constituted by the figure of the dragon and the motif of the gryll.

Fabienne Fravalo

Curator of the Decorative Arts Collection

Fondation Gandur pour l'Art, April 2024

Notes and references

- We would like to thank Emmanuel Ussel for his research around this object, at the origin of this text.

- Pastoureau, Michel. “Avant-propos. Des animaux pour rêver” in Bouillon, Hélène (ed.), Animaux fantastiques. Du merveilleux dans l’art [exhibition catalogue, Lens, Musée du Louvre-Lens, 27 September 2023 – 15 January 2024]. Ghent: Snoeck, and Lens, Musée du Louvre-Lens, 2023, p. 17.

- Cf. Blanc, William. “Les mille visages des dragons” in Bouillon, Hélène (ed.), Animaux fantastiques. Du merveilleux dans l’art…, p. 220.

- Delacampagne, Ariane and Christian. Animaux étranges et fabuleux, Un bestiaire fantastique dans l’art. Paris: Citadelles et Mazenod, 2004, p. 134.

- Ibid.

- Blanc, William, “Les mille visages des dragons”,…p. 221.

- Arasse, Daniel. Le Portrait du Diable. Paris: Arkhê, 2010, p. 78.

- Ussel, Emmanuel. Coupe (lavamano) à décor de diables (FGA-AD-OBJ-0023), notice, Geneva: Fondation Gandur pour l’Art, 2016 (unpublished).

- Cf. Malgouyres, Philippe. “L’invasion des satyres” in De Filarete à Riccio. Bronzes italiens de la Renaissance (1430-1550). La collection du musée du Louvre. Paris: Louvre éditions and Mare & Martin, 2020, p. 213-230.

- Lissarague, François. “Faunes et satyres, triviales poursuites” in Papin-Drastik, Ivonne (ed.). Faune, fais-moi peur! Images du faune de l’Antiquité à Picasso, [exhibition catalogue, …]. Cinisello Balsamo; Milan, Silvana Editoriale, 2018, p. 42.

- Arasse, Daniel. Le Portrait du Diable,… p. 30-31.

- Cf. Melot, Michel. “La fabrique du monstrueux” in Harent, Sophie and Guédron, Martial (ed.). Beautés monstres. Curiosités, prodiges et phénomènes, [exhibition catalogue, Nancy: Musée des Beaux-Arts, 24 October 2009 - 25 January 2010]. Nancy: Musée des Beaux-Arts; Paris: Somogy éditions d’art, 2009, p. 30.

- Cf. Fravalo, Fabienne. “Lavamano à décor de diables” in Estaquet-Legrand, Alexandre; Terrin, Jean-Jacques; Verbeke, Gautier (ed.). Mondes Souterrains [exhibition catalogue, Lens: Musée du Louvre-Lens, 27 March – 22 July 2024]. Ghent: Snoeck, and Lens, Musée du Louvre-Lens, 2024, p. 210-211.

- Le Goff, Jacques. Preface in Baschet, Jérôme. Les Justices de l’au-delà. Les représentations de l’enfer en France et en Italie (XIIe-XVe siècle). Rome: École Française de Rome, Palais Farnèse, 1993, p. XIV.

- Ussel, Emmanuel. Coupe (lavamano) à décor de diables…

Bibliography

Arasse, Daniel. Le Portrait du Diable. Paris: Arkhê, 2010.

Baschet, Jérôme. Les Justices de l’au-delà. Les représentations de l’enfer en France et en Italie (XIIe- XVe siècle). Rome: École Française de Rome, Palais Farnèse, 1993.

Bouillon, Hélène (ed.). Animaux fantastiques. Du merveilleux dans l’art [exhibition catalogue, Lens, Musée du Louvre-Lens, 27 September 2023 – 15 January 2024]. Ghent: Snoeck, and Lens, Musée du Louvre-Lens, 2023.

Delacampagne, Ariane and Christian. Animaux étranges et fabuleux, Un bestiaire fantastique dans l’art. Paris: Citadelles et Mazenod, 2004.

Estaquet-Legrand, Alexandre; Terrin, Jean-Jacques; Verbeke, Gautier (ed.). Mondes Souterrains [exhibition catalogue, Lens, Musée du Louvre-Lens, 27 March – 22 July 2024]. Ghent: Snoeck, and Lens, Musée du Louvre-Lens, 2024 (notice by F. Fravalo, p. 210-211).

Guédron Martial. Les Monstres. Créatures étranges et fantastiques, de la préhistoire à la science- fiction. Paris: Beaux-Arts éditions, 2018.

Harent, Sophie and Guédron, Martial (ed.). Beautés monstres. Curiosités, prodiges et phénomènes, [exhibition catalogue, Nancy, Musée des Beaux-Arts, 24 October 2009 – 25 January 2010]. Nancy: Musée des Beaux-Arts; Paris, Somogy éditions d’art, 2009.

Malgouyres, Philippe. “L’invasion des satyres” in De Filarete à Riccio. Bronzes italiens de la Renaissance (1430-1550). La collection du musée du Louvre. Paris: Louvre éditions and Mare & Martin, 2020, p. 213-230.

Ussel, Emmanuel. Lavamano à décor de diables (FGA-AD-OBJ-0023), notice, Geneva, Fondation Gandur pour l’Art, 2016 (unpublished).