May 2023 Ethnology

Producing airflow with grace and majesty:

Fan from the Marquesas Islands

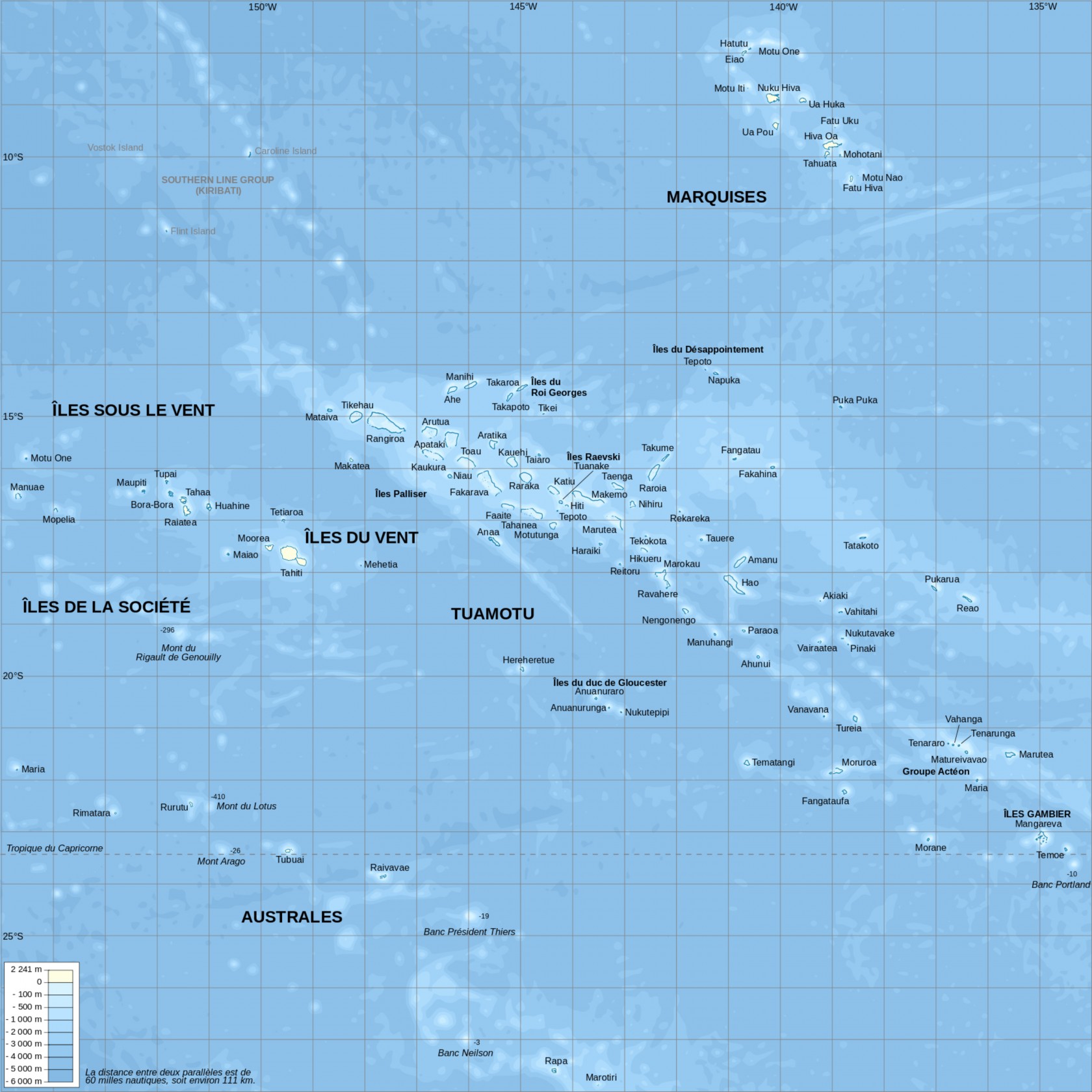

The weaving of vegetable fibres, the Polynesian art par excellence, has reached perfection in the Marquesas Islands. Associated with a refined carving, it turns the fan into a prestigious symbol, which aroused the admiration of the first visitors to Eastern Polynesia (fig. 1). The Fondation Gandur pour l'Art is lucky to have a fine exemplar, which time and wear have made atypical.

See the artwork in the collectionFan

Polynesia, Marquesas Islands, half of the 19th century

Ironwood, vegetable fibre

44 x 40 cm

FGA-ETH-OC-0083

Provenance

Collected in 1894-1895 by Herbert J. Allcroft

Collection Herbert J. Allcroft, Stokesay Court, Shropshire, Angleterre

Collection Wayne Heathcote, New York

Private collection, New York

Bonhams, New York, sale of the 27.04.2022, lot n°13

Galerie Flak, Paris

Acquired at the galerie Flak, Paris, 5 July 2022

A fan which has lived

Our collection of Oceanian art was recently enriched with one of these precious Marquesan fan (tahi’i); this one can be identified among many by its small V-shaped gap in the middle of its upper rim, a lacuna witnessing the long life spent in the hands of Marquesan chiefs or chiefesses. A weakness – some would say a defect – which makes this piece unique by giving it the majestic and ethereal appearance of a whale tail. An object which, like a human face, carries the marks of time: the scars seen on the sides of the blade, as well as the nice wear patina of its carved wood handle, would have many stories to tell about the hands which held it, the airflow it produced, and the ceremonies carried out around it.

Portrait of a chieftain carrying a fan

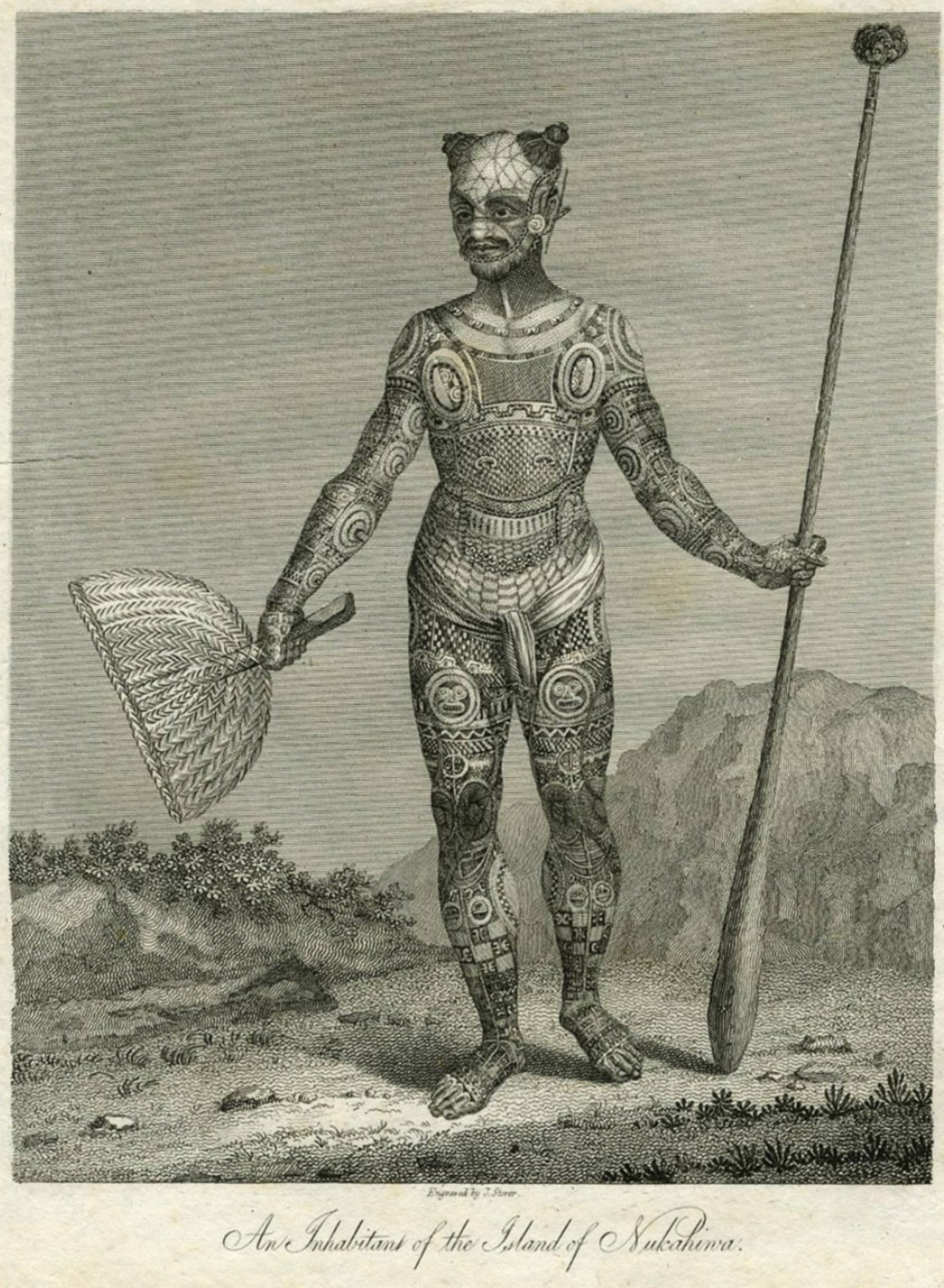

Sketches and reports brought back by travellers of the 19th century all pulsate with the flutter of these fans. Its first appearance in the iconography dates back to 1813, on an engraving of the naturalist Wilhelm Gottlieb Tilesius von Tilenau: the fan held in the right hand of a tattooed chieftain from Nuku Hiva, who is holding a tokotoko pio’o or chief staff in his left hand (fig. 2) 1. A few decades later, the reports and illustrations by Max Radiguet – secretary of the admiral Abel Aubert Dupetit-Thouars, who was on a mission to the Marquesas from 1841 to 1845 –, along with the watercolours of the missionary Clarissa Chapman Armstrong, form the main source of information on the insignia regalia of the Marquesan chieftains, to whom the tahi’i belongs. In 1833, Clarissa Armstrong depicts Tamahitu, the king of Nuku Hiva (fig. 3), wearing a headdress and ear ornaments, holding the white fan and wearing a red cloak, a colour only used by men of high status. This type of portrait of a chief “with a fan” is taken over a few years later by Max Radiguet who, in 1842, depicts in the same way another chieftain from Nuku Hiva (fig. 4). During a gathering, “any kind of chief would carry a broad white fan” 2. This speaks volumes on the importance of this symbol as a mark of social status.

“Pakoko stepped towards his judges, greeting them with his fan”

Indeed, a fan is first used to express a rank: it is thus in the centre of another scene depicted by Radiguet, where it is shown between a king (perhaps Iotete, king of Tahuata) or a high priest and admiral Dupetit-Thouars. In 1845 Pakoko, the rebel warlord of Nuku Hiva, would fiercely greet with his fan the judges who just sentenced him to death3, and by refusing to be blindfolded, leaning on his staff and rising his fan once more, “as in the days when he would give the signal for the comumus (singings)”4, he dies as a chief. Finally, another fan is graciously held by Vaekehu, queen of Nuku Hiva, on a drawing by Julien Viaud (Pierre Loti) produced in January 1872 (fig. 5), which inspired an engraving published in L’Illustration in October 1873. Fans were transmitted from a generation to the next – and as to the tahi’i of queens, from woman to woman5.

Chieftains would hold it, wave it, use it as a sunshade6, raise it as a sign of greeting or resistance, or to command the beginning of chants: in other words, the white fan claims the natural authority of its owner and their ancestry7. Precious and delicate as the wings of a butterfly, the only part preserved is often the handle, without the woven blade.

The Marquesan perfection

If fans from the Society Islands, the Cook Islands, Tahiti or the Austral Islands are triangular, elongated or even heart-shaped, the blade of the Marquesan fan is spread as a semi-ellipse formed from a very minute and tight woven sheet8. Apart from its shape, what distinguishes the tahi’i from other fans is the extreme thinness of its weaving, which enables the production of a very flexible sheet. The wave produced by the user is thus perfectly distributed on the delicate weaving9. The woven sheet was then whitened with shell or coral lime for protection from insects10, a treatment which had to be reapplied on a regular basis, thus reviving its dazzling whiteness11. Perhaps a life-saving colour, as it is possible that the white object held by the very first Marquesan man met by the Spaniards in 1595 at Hiva Oa, then interpreted as a sign of peace, was actually a fan12.

A forgotten know-how

This art, which reached its peak in the 19th century in the Marquesas, is widely distributed in Polynesia, notably in Tahiti, and in the Austral Islands, where it was a feminine know-how transmitted from mother to daughter13. However, in the Marquesan Islands, these pieces of weaving were so complex that they were only produced by specialists.

In the highly hierarchical and formal society of these islands, these objects were produced in secrecy by specialists (tuhuka or tuhuna), as they had to be aesthetically perfect since they were meant to be used by high-ranking people, such as queens, kings, chieftains of small communities, or even priests. This need for perfection was presiding over the fabrication of any prestige object meant for a member of the elite: a master would never try to repair an object displaying the smallest defect; the imperfect object was relentlessly abandoned, and the master would produce a new one14. Time did not matter, the only important thing was the perfection of the piece produced.

The carved handle thus pertained to the work of the tuhuka ketu kee tahii and the woven blade to that of the tuhuka aaka tahii. A skilful basketwork technique, passed on from one generation to the next, so refined that it resembles weaving, but which somehow got lost. As we could see with other Oceanian objects, notably the Kiribati armour15 or the Tonga weavings16, art is first used to capture the divine within complex knots, fibre intertwinings, crossings of stems, mazes of links.

With the passing of the last tuhuka, this know-how fell into oblivion. The technical aspect is not the only one which disappeared with it, as we can also wonder whether certain elements (size of the blade, choice of the fibres, material and decoration type of the handle, etc.) could enable a distinction among the tahi’i of a king, queen, chief, or chiefess. Unfortunately, this historical knowledge was also lost.

Medical imaging helps to restore a lost craft

Today, analyses pertaining to medical imaging, notably X-ray computed tomography and 3D microscopy, enable to understand how these masterpieces were produced17: a research carried out on eight fans of the Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac shows that the carved handle was extended to form the axis of the fan, around which the sheet was woven, according to the waling technique.

Without going into technical detail, for which these researches must be consulted, one can say that the handle forms the backbone of the fan, around which the sheet was spread. Overbraiding cords made of coconut fibre were coiled around the handle to ensure the sturdiness of the whole object. The aspect of these cords at their onset, with two cords united followed by chevrons, is also typical of the Marquesan way of weaving18. As for the weaving of the sheet, it is very tight around the handle, and becomes more loose as we move away from the axis19. The sheet is made in “cross twill weave”, with the crossing of horizontal weft strands on vertical warp strands used as support20. The fibres follow a curve, allowing the gradual widening of the sheet, so as to obtain its typical semi-oval shape.

The edge of the fan

A summit stripe seals the fan by incorporating the end of the vegetable strands. In the present case, this stripe consists of four horizontal plaits closing the blade of the fan on its entire length. This technique is the most frequently seen on the fans preserved at the Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac21. The second of the three techniques seen, consists of two double horizontal braids encircling two stripes of vertical weave, the edge showing four thin horizontal braids in total22. Finally, the third technique consists of a single horizontal braid closing the blade.

These variants could be hallmark of different workshops23, probably located on Tahuata Island, which is famous for the quality of its fans. James Cook brought back several exemplars from this place. In 1835, the whaler F. Bennett saw in Tahuata these large semi-circular fans made of the ribs of coconut leaves softened by heating, which are typical for the island’s aristocracy, he says24. In fact, only a botanical study of the material would enable to identify whether we are dealing with leaves of coconut, pandanus or Pelagodoxa henryana, a palm tree endemic to the Marquesas Islands also known as ‘enu or vahake, and whose leaves were reserved for the fans of high-ranking individuals25.

Under the protection of Tiki

The handles of the first fans collected by James Cook at Tahuata were simply polished and flared at their end. Sometimes this end was adorned with a knob made of human bone or ivory. Over time, the handle, made of wood (sandalwood or ironwood, toa), sperm whale ivory or human bone, becomes more elaborate, with the carving of two superimposed pairs of tiki, usually placed back-to-back, in a Janus-like manner. Placed above, below and between the pairs of tiki are cushions of crenelated hoops, which form the pattern of the whole: these hoops may result from the gradual transformation of the etua pattern, a stylised repetition of hands and feet26. An attractive and practical handle, which also enabled to roll the fan between one’s fingers, enabling its royal owner to animate the tiki, thus activating their mana27, the supernatural force proper to Oceanian deities.

The main character, from whom the object draws its entire power, is of course Tiki. As a deified ancestor, he appears in the entire Polynesian art, as he was the first human being, and with his wife he had made out of sand, he fathered many children, and created the islands28.

The Marquesan aesthetics of the tiki makes it a small being with a large head (which is one third of the total height of the figure), oversized almond-shaped eyes, and a small nose with broad nostrils. His ears, which are almost as high as the entire head, are shown by a spiraled line. The figure does not display clearly marked sexual characteristics.

Head, eyes, mouth and ears are all endowed with a supernatural power, since they are the seat of the sacred power of the tiki, and related to his ability to see (eyes), to the breath and energy of life (nose), and sexuality (ears). The defiantly broad mouth expresses the certainty of victory, and thus brings protection29. In its most frequent position, the figure is shown with hands placed on the knees.

In the present case (fig. 6), the pair of tiki close to the tip of the ironwood handle bring their hand to their chin, which is usually merged with the elongated mouth. This rather rare detail is also seen on two other fans of the Garnier collection, acquired in 1868 by the enseigne de vaisseau Martial Pescheloche during a sojourn in Tahiti and the Marquesas30. What is the meaning of this gesture, and of this superimposed pairs? According to Anne Lavondès, these pairs, which may be of both sexes, probably refer to an ancient Polynesian mythology, or to the founding ancestors of the group31.

The mischievous skinks of the Marquesas

The most ancient of these fans, gathered from 1820 to 1850 but produced long before, display handles with very worn reliefs; the space between the back-to-back tiki is not hollowed out, a feature which only appeared with later fan handles. At the tip of the handle, the presence of two animal heads with large round eyes, like those of lizards (which are well attested in Marquesan iconography)32, with long pointed nose forming a kind of anchor, is also typical of a later production33.

An inspiring beast, also found on other prestige artefacts, such as the U’u sceptres. Lizards are ubiquitous on these islands, notably geckos and skinks34, and the latter probably aroused these depictions. With humour, Karl von den Steinen even reports that while he was inspecting a marae (sacred place), a lizard hidden in a human skull suddenly jumped on his face, a mishap which also occurred to one of his colleagues, who was so surprised by the reptile that he immediately dropped the skull he was holding, as if it were glowing embers35.

The tahi’i of the FGA, collected by H.J. Allcroft during a leisure trip in Polynesia in 1894–1895, pertains to this type of fan.

Tahi’i: when skills and love for perfection exalt the simplicity of natural materials.

Dr Isabelle Tassignon

Curator of the Ethnology collection

Fondation Gandur pour l’Art, May 2023

Notes and references

- KJELLGREN, IVORY, Adorning the World, p. 56-57.

- RADIGUET, Les derniers sauvages, p. 169.

- LAVONDÈS, “Tahii, éventail”, p. 158; RADIGUET, Les derniers sauvages, p. 250-251.

- LAVONDÈS, “Tahii, éventail”, p. 158; RADIGUET, Les derniers sauvages, p. 250-251.

- KAEPPLER, KAUFMANN, NEWTON, L’art océanien, p. 532.

- RADIGUET, Les derniers sauvages, p. 15.

- “In the Marquesas Islands, saying that an individual was ‘carrying the fan’ meant that he was the chief”: after CAUCHOIS, Tressage, p. 63.

- CAUCHOIS, Tressage, p. 73. VON DEN STEINEN, Les Marquisiens et leur art, II, p. 71, mentions the presence in the Marquesas Islands, at Nuku Hiva, of diamond-shaped fans, and that he saw at Atuona a heart-shaped fan called Kiimata (‘eye skin’, in other words the eyelid), probably called so because of its shape.

- CAUCHOIS, Tressage, p. 73.

- VON DEN STEINEN, Les Marquisiens et leur art, II, p. 72.

- KJELLGREN, IVORY, Adorning the World, p. 81.

- LAVONDÈS, “Tahii, éventail”, p. 158.

- CAUCHOIS, Tressage, p. 152.

- OTTINO-GARANGER, “Fenua Enata”, p. 143.

- https://www.fg-art.org/en/artwork-of-the-month-archives/the-art-of-armour-in-kiribati

- https://www.fg-art.org/en/artwork-of-the-month-archives/seven-blunt-wonders-from-tonga-and-fiji

- KERFANT, MÉLANDRI, MOULHERAT, “Pour une restitution…”, pass.

- LAVONDÈS, in PANOFF, Trésors des îles Marquises, p. 106.

- KERFANT, MÉLANDRI, MOULHERAT, “Pour une restitution…”, p. 5, 12.

- KERFANT, MÉLANDRI, MOULHERAT, “Pour une restitution…” p. 8, 23; LAVONDÈS, in PANOFF, Trésors des îles Marquises, p. 118.

- For these questions, see KERFANT, MÉLANDRI, MOULHERAT, “Pour une restitution…”, p. 9, 24.

- This technique can be clearly seen on a fan of the Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, inv. 71.1887.31.23: https://www.quaibranly.fr/fr/explorer-les-collections/base/Work/action/show/notice/1978-eventail.

- KERFANT, MÉLANDRI, MOULHERAT, “Pour une restitution…”, p. 9, 25.

- LAVONDÈS, in PANOFF, Trésors des îles Marquises, p. 118; LAVONDÈS, “Tahii, éventail”, p. 158.

- CAUCHOIS, Tressage, p. 71. For the leaves of Pelagodoxa henryana reserved for high-ranking persons: KERFANT, MÉLANDRI, MOULHERAT, “Pour une restitution…”, p. 13, 35.

- MU, in PANOFF, Trésors des îles Marquises, p. 118; VON DEN STEINEN, Les Marquisiens et leur art, II, p. 192-194.

- THOMAS, BURNT, in THOMAS, BURNT, Océanie, p. 300-301.

- GEOFFROY-SCHNEITER, in IVORY, Mata Hoata, p. 24-26.

- OTTINO-GARANGER, “Fenua Enata”, p. 128.

- GARNIER, LAVONDÈS, “Une collection privée”, p. 205-206, n° 4 et 5.

- LAVONDÈS, in PANOFF, Trésors des îles Marquises, p. 118.

- VON DEN STEINEN, Les Marquisiens et leur art, II, p. 118-119.

- LAVONDÈS, in PANOFF, Trésors des îles Marquises, p. 118.

- INEICH, “Reptiles terrestres…”, p. 369 sq.

- VON DEN STEINEN, Les Marquisiens et leur art, II, p. 119.

Bibliography

Cauchois, Hinanui, Tressage. Objets, matières et gestes d’hier et d’aujourd’hui, Tahiti, Au vent des îles, 2013.

Garnier, Henri, Lavondès, Anne, “Une collection privée. Objets des îles Marquises et documents”, Journal de la Société des Océanistes, 40 (1979), p. 199-214.

Geoffroy-Schneiter, Bérénice, “Au commencement était Tiki”, in Ivory, Carol (dir.), Mata Hoata, p. 26-33.

Handy, Craighill, Willowdean, Chatterson, L’art des îles Marquises, Paris, Les éditions d’art et d’histoire, 1938.

Hiquily, Tara, Vieille-Ramseyer, Christel (dir.), Tiki. Exposition Tiki, Musée de Tahiti et des îles-Te Fare Manaha, 15.09.2016 – 19.03.2017, Tahiti, Au vent des îles, 2016, p. 158-160.

Hooper, Steven, Pacific encounters. Art and Divinity in Polynesia, 1760-1860, London, British Museum Press, 2006.

Ineich, Ivan, “Reptiles terrestres et marins des îles Marquises : des espèces communes mais des populations isolées », in Galzin, René, Duron, Sophie-Dorothée, Meyer, Jean-Yves (éds), Biodiversité terrestre et marine des îles Marquises, Polynésie française, Paris, Société française d’ichtyologie, 2016, p. 365-390.

Ivory, Carol (dir.), Mata Hoata: arts et sociétés aux îles Marquises, Musée du quai Branly, Mata Hoata. Art et société aux îles Marquises, Paris, Actes Sud, 2016 (Connaissance des arts, hors-série n° 706).

Kaeppler, Adrienne L., Kaufmann, Christian, Newton, Douglas, L’art océanien, Paris, Citadelles & Mazenod, 1993.

Kerfant, Céline, Mélandri, Magali, Moulherat, Christophe, “Pour une restitution d’un patrimoine (re)naissant : méthodes d’analyse et perspectives de l’imagerie numérique 3D sur un corpus d’éventails des îles Marquises”, In situ, 39 (2019). Online: https://journals.openedition.org/insitu/21725?lang=en

Kjellgren, Eric, Ivory, Carol S., Adorning the World: Art of the Marquesas Islands, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2005.

Lavondès Anne, “Tahii, éventail”, in Hiquily, Vieille-Ramseyer (dir.), Tiki, p. 158-160.

Ottino-Garanger, Pierre and Marie-Noëlle, “Fenua Enata : la Terre des Hommes”, in Sivadjian, Ève (dir.), Les îles Marquises. Archipel de mémoire, Paris, Autrement, 1999, p. 116-143.

Panoff, Michel (dir.), Trésors des îles Marquises. Catalogue d’exposition, Musée de l’Homme, Paris, 1995.

Radiguet, Max, Les dernies sauvages. La vie et les mœurs aux îles Marquises 1842 à 1859, La Rochelle, Éditions La Découvrance, 2014. Originale ed.: Revue des Deux Mondes, 22 (1859), p. 421-479 and 23 (1859), p. 607-644.

Thomas, Nicholas, Burnt, Peter (dir.), Océanie. Exhibition catalogue, Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Paris, 12 mars – 7 juillet 2019, Paris, 2019.

von den Steinen, Karl, Les Marquisiens et leur art. Étude sur le développement de l’ornementation primitive des mers du Sud d’après les résultats personnels de voyage et les collections des musées, II. Plastique, original German edition, 1928; French edition, 2005; new edition, Tahiti, Au vent des îles, 2016.