September 2023 African Contemporary Art and of the Diaspora

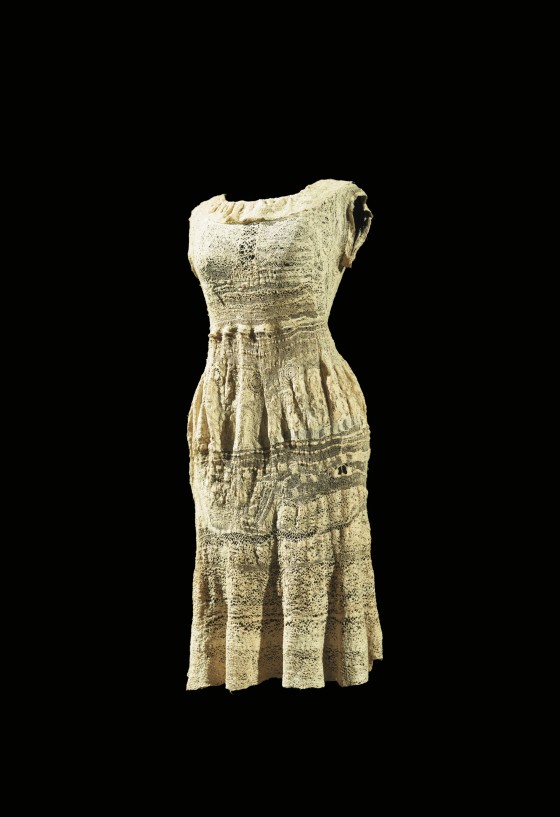

Dear Fesmeri and Mareni, the dress doesn’t fit III

by Georgina Maxim

Tenacity, a keen sense of composition and care are among the qualities essential to the execution of Georgina Maxim's work. These qualities are on full display in Dear Fesmeri and Mareni, the dress doesn't fit III, whose title is a metaphor to a letter, here addressed to the artist's mother and grandmother. Fabrics and laces found by Georgina Maxim in the wardrobes and storerooms of relatives–originally the wardrobe of her grandmother, Fesmeri– are transformed into agile sculptures, translating a family and collective narrative that takes shape stitch by stitch, fold by fold. The movement of the hand, holding the needle and pricking between the stitches, becomes a privileged means of expression1. A working methodology that withstands the test of time and overproduction, that reuses the materials worn by loved ones with accuracy and sometimes humor, and that addresses qualities historically associated–not to say assigned–to women.

See the artwork in the collectionGeorgina Maxim (Harare, Zimbabwe, 1980)

Dear Fesmeri and Mareni, the dress doesn’t fit III

2022

Textile, mixed media

116 x 60 x 10 cm

FGA-ACAD-MAXIM-0001

Provenance

Artist’ Studio

31 Project, Paris, 2022

Textile genealogies

"I wanted to invent a new way of honoring my grandmother's memory."2 Since inheriting her grandmother's wardrobe 15 years ago, Georgina Maxim has drawn on it as an inexhaustible source of inspiration, giving shape to several series of textile works. In the artist's eyes, garments linked to the presence and physicality of those who wore them are walking narratives that she gathers and links together. Embroidery, sewing, weaving, crocheting, cutting, assembling, folding and stitching revive the memory of that “lucky dress" worn by someone close to her, of that "garment-compliment" that suited them so well, or of that doll they dragged everywhere as a child, and seal their stories with thread.

From the loss of a loved one, and of the being who embodies feminine genealogy and heritage, Georgina Maxim closes the wounds, work after work, of a mourning that one would take care of every day. "Healing materializes for me", she declares. Far from the superficial dimension often associated with clothing, it is the attachment to materials as vehicles of remembrance that are at the heart of the device here. The title of the work, Dear Fesmeri and Mareni, the dress doesn't fit III, opens like a letter with words addressed to the artist's grandmother and mother respectively. "The dress doesn't fit", Georgina Maxim protests, implying the overwhelming feeling and incomprehension resulting from the female condition and all the expectations generated by it. The dress thus becomes a symbol of the roles left behind by the women in her lineage: grandmother, mother, sister, wife, woman. However much Georgina Maxim tries to wear them, pull them on, alter them, transform them, "the dress doesn't fit", she says, paradoxically rejecting the feminine condition while at the same time using one of its most widespread apparatuses (domestic chores, embodied here in sewing).

Three little dots... of healing

Georgina Maxim describes her practice through three ways of understanding the stitches that give shape to her works: "laughter" stitches (those that appear on the waist after too much of it); "sewing" stitches (those that the gesture of her hand literally executes between materials); and stitches in scars (those that close wounds).

Each of these stitches is an integral part of her work, which has taken her from laughter to sewing, and healed her scars in the process. All these elements evoke the bonds to her beloved mother and grandmother, the complicity, the traces of mourning, but also the domestic chores that women perform from generation to generation, those gestures of care reserved for women that eras reproduce, at least in part.

A graduate of the University of Bayreuth in African Verbal and Visual Arts, she also has a degree in painting from the University of Chinhoyi, and is surrounded by painters in her daily life–including her partner and co-founder of the Unhu Village art space in Harare, Misheck Masamvu. Her practice is as much about the intelligence of the hand as that of a painter. There is no utility in the artist's stitches, which are akin to brushstrokes on a canvas. Her works cannot be worn like clothes and she obviously doesn't use machines to give shape to her works, the thread guiding her intuitively from one material to another.

Feminism and textiles: practices on the thread

If textile arts are "historically part of women's lives", as art historian and critic Aline Dallier- Popper asserted in 1976 already3, the broader history of textile materials in contemporary art includes work by artists such as Sheila Hicks, heir to Bauhaus modernism and practitioner of a textile art drawing on pre-Columbian techniques, as well as the sculptural works of Magdalena Abakanowicz4, who made thread her most powerful means of expression5. From "Woven Forms" to "Art Fabric[s]" and "Soft Art", the history of textiles' shift from the sphere of craft to that of art accompanies the avant-gardes of the late 19th century and the decompartmentalization of artistic practices in the 1960s. But it also corresponds to the increased presence of women in exhibitions, determined to get their foot in the door without letting it close, and buoyed by the feminist wave of the 1970s, which established the legitimacy of fabrics in contemporary exhibition spaces.

The association of ideas and forms between women, feminism and textiles in art is thus the result of a triple movement. Firstly, women are giving their letters of nobility to these materials linked to the domestic tasks that are part of their lives, seeing them as legitimate means of expression. Indeed, Georgina Maxim's work promotes the skills involved in working with textiles, challenging the artisanal and hobbyist vision associated with the latter. Secondly, these tasks have been assigned to women as a result of the separation of roles in many societies, leaving them to carry out work in the home. Thirdly, until the mid-twentieth century, the art world and its training schools had difficulty opening their doors to female candidates. For example, the only workshop at the Bauhaus (the renowned school of architecture and applied arts founded in 1919 in Weimar, Germany, yet founded on principles of equality) open to women on an unlimited basis was the textile workshop6. It was here that Anni Albers (1899-1994), a German artist who settled in the United States in 1933, worked extensively with these materials, and is often cited as one of the pioneers in the visual arts and the use of fabrics.

Balancing on a tightrope, these practices traverse the history of art and its links to women and feminism, sometimes viewed with condescension, sometimes with complacency, and sometimes traversed by revolutions.

Textile arts from Harare to Lausanne

On the occasion of her first international residency at the Embassy of Foreign Artists in Switzerland, Georgina Maxim made a landmark visit to the Collection de l'Art Brut in Lausanne. Not only was she moved by the meticulousness with which the wedding dress by Marguerite Sirvins (1890-1957) (fig. 2) was executed, but also by the physical manifestation of this act of marriage, constantly postponed by the titanic work demanded by the crochet stitch and created with sewing needles and thread pulled from pieces of used linen. What we now nobly call the textile arts, which were featured at the Biennale de la Tapisserie de Lausanne from 1962 to 19957, have left many tangible marks on the Swiss city, and were the subject of a symposium in 2009, followed by a collective publication entitled Metatextile. Identity and History of a Contemporary Art Medium. But while the main artists represented at the 16 Biennales held in Lausanne have mainly come from the European and American continents–including a spectacular turnout of Polish artists, who are part of a revival of taste for these artistic productions–only Fatma Charfi M'Seddi is recorded as representing Tunisia in the 1992 edition8.

The example of Anni Albers–constrained to only attend the Bauhaus textile workshop–thus brought the question of gender into play in the use of textile materials, while an intersectional dimension is highlighted by several works, notably those by Agnes Buys Yombwe9, Ghada Amer and Faith Ringgold. Faith Ringgold, a Harlem artist who also paints, turned to textiles for her "story quilts" because they have always been associated with domestic work, women's work and African-American crafts, as practiced by her mother and grandmother10. Art historian Alissa Auther notes that "(...) Faith Ringgold's exploration of the divide between art and craft demonstrated that these relationships were influenced not only by gender but also by race, thus extending the feminist critique of aesthetic hierarchy beyond its link to the domestic sphere"11. Ringgold's quilts thus became the privileged site of memory of the Harlem Renaissance and of interracial violence in the United States. Cotton-related textile production and slavery in America were mutually dependent, as historian Jessica Hemming argues.

Georgina Maxim pursues the path of creation through the textile arts, using the plastic, physical and memorial qualities of these materials and calling on our senses to imagine the contact of materials and the interweaving of threads as so many stories that intersect and create the fabric of a common narrative.

The context of the city of Harare and Georgina Maxim's personal experience are therefore totally distanced from this particular history, as memory does not require figurative representation and emblematic figures, such as those of Ringgold for the Harlem Renaissance. Georgina Maxim pursues the path of creation through the textile arts, using the plastic, physical and memorial qualities of these materials and calling on our senses to imagine the contact of materials and the interweaving of threads as so many stories that intersect and create the fabric of a common narrative. As Professor Stefania Caliandro has said of Brazilian creation in the 1960s, Maxim is also developing less "an art of the body (body art) than an art of relationships woven by bodies"12.

Olivia Fahmy

Curator, collection of African Contemporary Art and of the Diaspora

Fondation Gandur pour l’Art, September 2023

Notes and references

- KAZUNGU, Martha, “Georgina Maxim: When Patience Becomes Artistic Currency”, in Contemporary &, May 2 2019, https://www.sulger-buel-gallery.com/news/25-contemporary-and-c-features-georgina-maxim-whenpatience-news/

- LEPERT, Mathilde, « Guérir point par point. Interview avec Georgina Maxim », in Le Journal des Rencontres AKAA, 2019, [online:] https://issuu.com/akaafair/docs/pdf_planches/s/167867 (consulted on 23.06.2023)

- Quoted in SABAU, Julie, « L’art textile », AWARE, 01.02.2018 [online:] https://awarewomenartists.com/decouvrir/textile-art/(consulted 12.07.2023).

- On view at the Musée Cantonal des beaux-arts de Lausanne this Summer 2023, in a joint exhibition with Tate Modern, London.

- BILLETER, Erika, « Quelques points lancés dans l’histoire de l’art moderne du textile », in Collection de l’association Pierre Pauli. Art textile contemporain, Musée des arts décoratifs de la Ville de Lausanne, Lausanne, 1983, p. 9.

- GONNARD, Catherine, “Anni Albers” [notice], AWARE, 2013 [online:] https://awarewomenartists.com/artiste/anni-albers/ (consulted on 02.08.2023).

- See: http://www.toms-pauli.ch/fondation/presentation/.

- According to the City of Lausanne website, "The Centre international de la Tapisserie Ancienne et Moderne (CITAM), founded in Lausanne in June 1961, has aimed to capture, document and above all showcase, through the organization of the Biennales internationales de la Tapisserie, the vitality and creativity of contemporary tapestry." Their database is available online: https://cindocwebinternet.lausanne.ch/cindocwebjsp/?bc=assistedquery&uid=citam&pwd=archives&pid=931&&archive=Citam.

- See in particular MULENGA, Andrew M., "Agnes Buya Yombwe", AWARE [online:] https://awarewomenartists.com/artiste/agnes-buya-yombwe/ (consulted on 12.07.2023).

- Street Story Quilt, Faith Ringgold, American, 1985 [notice, en ligne] Metropolitan Museum New York, available at the address https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/485416 (consulted on 04.07.2023)

- AUTHERS, Alissa, String, Felt, Thread: The Hierarchy of Art and Craft in American Art, Minneapolis, MN:

University of Minnesota Press, 2010. p. 100, quoted in HEMMINGS, Jessica, “That’s Not Your Story: Faith Ringgold Publishing on Cloth”, in Parse, n° 11, 2020 [online:] https://parsejournal.com/article/thats-not-yourstory-faith-ringgold-publishing-on-cloth/#post-6705-endnote-ref-14 (consulted on 07.07.2023). - CALIANDRO, Stefania, « De l’oeuvre d’art comme texte à la texture des oeuvres. Trames et parcours relationnels dans la création contemporaine brésilienne » in WEDDING, Tristan (ed.), Metatextile: Identity and History of a Contemporary Art Medium, Berlin : Edition Imorde, 2010, p. 87.

Bibliography

AUTHERS, Alissa, String, Felt, Thread: The Hierarchy of Art and Craft in American Art, Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

BILLETER, Erika, « Quelques points lancés dans l’histoire de l’art moderne du textile », in Collection de l’association Pierre Pauli. Art textile contemporain, Musée des arts décoratifs de la Ville de Lausanne, Lausanne, 1983, p. 9.

CALIANDRO, Stefania, « De l’oeuvre d’art comme textev à la texture des oeuvres. Trames et parcours relationnels dans la création contemporaine brésilienne » in WEDDING, Tristan (ed.), Metatextile : Identity and History of a Contemporary Art Medium, Berlin : Edition Imorde, 2010.

GONNARD, Catherine, “Anni Albers” [notice], AWARE, 2013 [en ligne]: https://awarewomenartists.com/artiste/anni-albers/ (consulted on 02.08.2023).

HEMMINGS, Jessica, “That’s Not Your Story: Faith Ringgold Publishing on Cloth”, in Parse, n° 11, 2020 [en ligne :] https://parsejournal.com/article/thats-not-your-story-faith-ringgoldpublishing-on-cloth/#post-6705-endnote-ref-14 (consulted on 07.07.2023).

KAZUNGU, Martha, “Georgina Maxim: When Patience Becomes Artistic Currency”, in Contemporary &, 02.05.2019 [en ligne:] https://www.sulger-buel-gallery.co/news/25- contemporary-and-c-features-georgina-maxim-when-patience-news/ (consulted on 23.06.2023).

LEPERT, Mathilde, « Guérir point par point. Interview avec Georgina Maxim », in Le Journal des Rencontres AKAA, 2019, [en ligne :] https://issuu.com/akaafair/docs/pdf_planches/s/167867 (consulted on 23.06.2023).

SABAU, Julie, « L’art textile », AWARE, 01.02.2018 [en ligne :] https://awarewomenartists.com/decouvrir/textile-art/ (consulted on 12.07.2023).

WEDDING, Tristan (ed.) et al., Metatextile : Identity and History of a Contemporary Art Medium, Berlin : Edition Imorde, 2010.