December 2021 Decorative Arts

"A Container of Light". Le vase de Pierre Soulages

As part of the exhibition In Praise of Light at the Fondation Baur (Geneva, 17.11.2021-27.03.2022), this vase, created by Soulages at the Manufacture de Sèvres, enters into a dialogue with the braided bamboo sculptures of Tanabe Chikuunsai IV, alongside four paintings by the French artist from the Fondation Gandur pour l’Art Collection.

This unique encounter provides an opportunity to situate this object at the heart of a corpus of work by the “Master of Black and Light”, as well as exploring his ties with the Land of the Rising Sun.

See the artwork in the collectionPierre SOULAGES

(Rodez, 1919)

Vase (known as the “Sèvres Vase” or “Soulages Vase”)

2000-2008

Sèvres porcelain (“new paste” porcelain), matt black and grey low-temperature enamels, 24-carat pure gold gilding and brass (edition 6/10)

66 x 34.5 cm

Signed and numbered under the foot “Soulages 6/10”; Sèvres Manufacture hallmarks “Sèvres 1 2” and “Décoré à Sèvres Manufacture nationale B T”

FGA-AD-OBJ-0089

Provenance

Galerie Bérès, Paris, 2014

Created and produced in collaboration with the Manufacture nationale de Sèvres, this vase, of ten copies exist today, is the result of Soulages’ interest in the applied arts, his pictorial work around black and light, and his affinities with the Land of the Rising Sun.

Soulages in Sèvres

In 1999, according to the wishes of then-President Jacques Chirac, Pierre Soulages was invited to design the decoration of a porcelain vase, produced in the workshops of the Manufacture de Sèvres. The vase was intended to be presented to the Nihon Sumō Kyōkai association, where it would be given as a trophy to the winner of the annual Nagoya Sumo Tournament.1 The artist decided upon a sober but classic form, based on a design by Maurice Gensoli dating from 1950, known as “Vase no. 11,” which Soulages intended to simplify. While he conserved the pedestal, he purified it by stripping it of its mouldings, and he removed the upper lip, but added a lid, which subsequently would be pierced laterally, just like one of the vertical sides of the vase, perforated with a large circle. This reinterpreted and modernized version of the vase was made in the large-scale casting workshop2 from “new paste” (pâte nouvelle), a 45% kaolin porcelain, developed in 1882, which provides great resistance to the deformations that may occur during firing at around 1,250°C. Once the form was developed, next came the decoration: plastic initially, and then enamel.

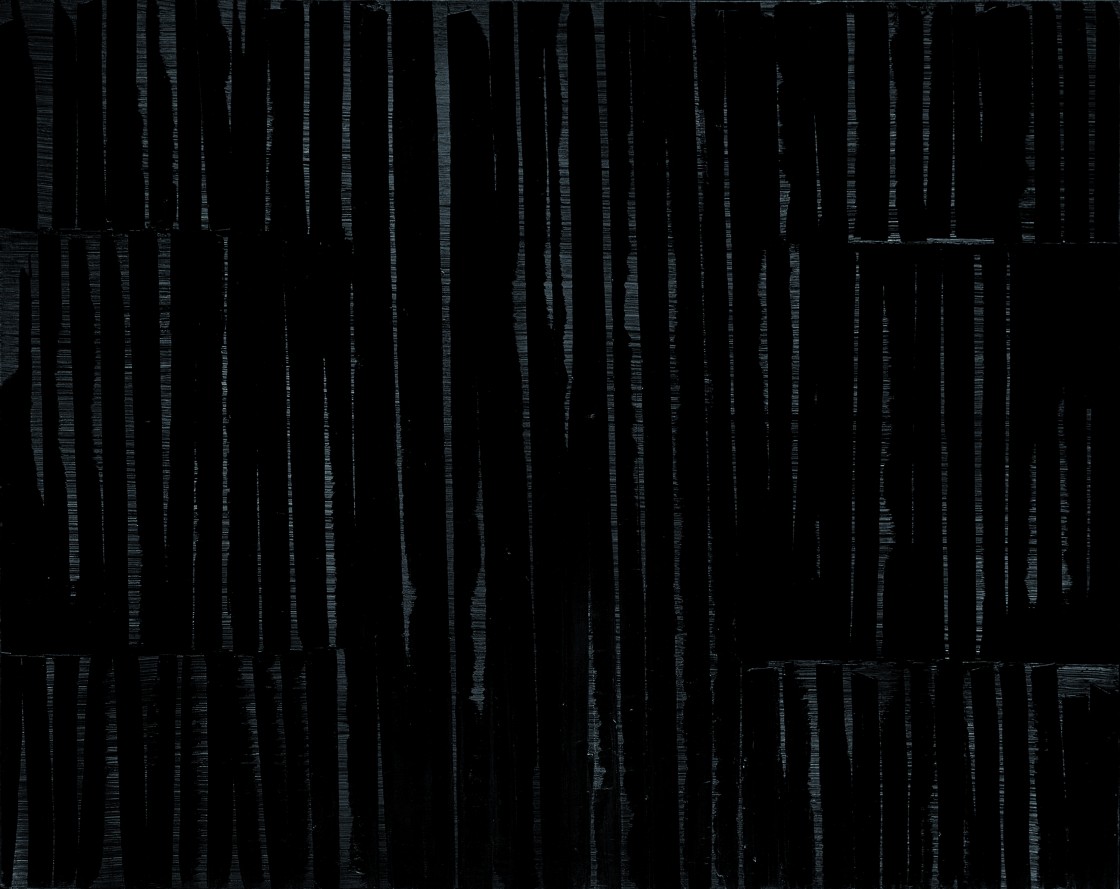

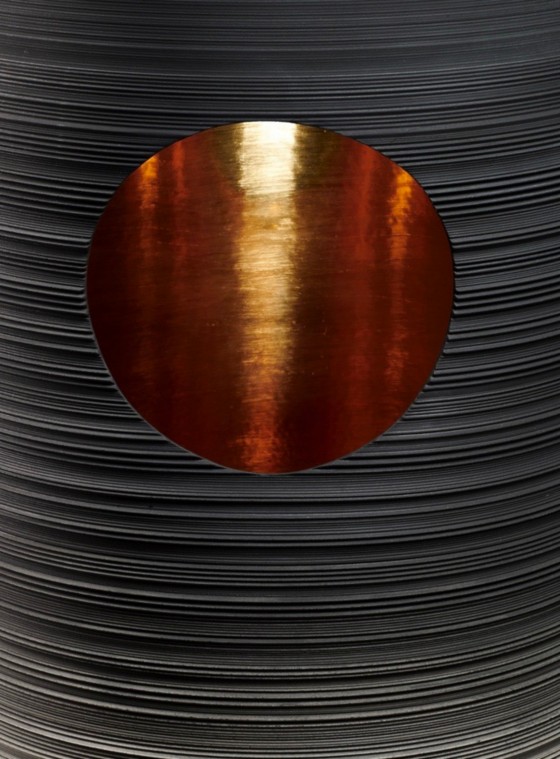

Fine horizontal ridges, of varying height and depth, were obtained by means of the tournasage3 technique, by rubbing a metal comb on the raw paste over the entire height of the vase (fig. 2), before a first firing at 960°C, followed by a passage in the kiln at 1,260°C to fix the enamel applied to the inside of the vase.

The central opening was then cut in several stages using a diamond wheel. A semi-matt black enamel, known as “Soulages black” specially created by laboratory manager Antoine d’Albis, was then applied before a final firing at 840°C. This deep and intense hue was applied with a wide flat brush, with the colour saturated in the upper part of the vase, then subtly degraded towards the lower section, gradually giving way to a grey-hued enamel.4

Continuing the tradition of the Manufacture, where collaborations with artists from outside the world of ceramics were common since its inception, Pierre Soulages skilfully used the technological means made available to him in the various workshops. His creation is a highly original reinterpretation of the Sèvres’ aesthetic, thanks to a form and decoration that are both singular and personal, and fully emblematic of his work. The “Soulages Vase” follows in the footsteps of the Manufacture’s previous collaborations with major contemporary artists, initiated in the 1960s under the aegis of André Malraux, Serge Gauthier and Antoine d’Albis, inviting artists such as Georges Mathieu, Alexander Calder, Maria-Helena Vieira da Silva and more recently, Pierre Alechinsky, Chu Teh-Chun and Zao Wou-Ki.5

Ceramic: an (almost) unknown material

This creation should be understood in light of Pierre Soulages’ previous forays into fields other than that of painting, in particular the applied arts. Indeed, the artist had previously experimented via various collaborations with a number of French Manufactures. There were, for example, the monumental tapestries made at Aubusson in 1963 for the Maison de la Radio, and at the Savonnerie from 1987 to 1991 for the Ministry of Finance. As was the case at Sèvres, while Soulages did not actually intervene in the manufacturing process, which was entrusted to specialized artisans, the painter designed each of these decorative projects, not only according to the place intended to receive it, but also by taking into careful consideration the properties of the material used to achieve the desired effects. In tapestry, the use of wool, which completely absorbs the light without reflecting it, therefore required the adoption of different types of materials and techniques so as “to obtain different depths of black, as well as modulations in the woven fabrics.”6 Likewise, for the stained glass windows for the abbey church of Conques, produced between 1986 and 1994, a special glass was developed in the Saint-Gobin laboratory, in order to create the exact translucency sought by the artist to best capture the light’s rays.

More than thirty years previously, Pierre Soulages had confronted, on a monumental scale, the reflective properties of glazed ceramics. In 1968, he created a vast wall decoration measuring 4.27 metres in height and 6.10 metres in width. This ceramic “fresco” was intended to adorn the lobby of a Pittsburgh skyscraper known as One Oliver Plaza, built by William Edmond Lescaze (1896-1969) for real estate developer Oliver Tyrone. The two men had met through art dealer Sam Kootz (1898-1982). The work was executed by Jean Mégard (1925-2015), a ceramist member of the Espace group, which in the 1950s brought together artists, architects and ceramists, like André Borderie, with the aim of promoting art in the urban environment. Entitled La Céramique, 14 mai 1968, the work consists of 294 hand-fashioned tiles made from chamotte clay7 on which there is an immense composition in black and dark blue, partially entwined with subtle variations in the palette, and whose forms reflected the light fixtures hanging in the same lobby 8.

In other words, Soulages’ links with the applied arts and the world of ceramics were already in existence, albeit primarily on a monumental scale. As early as 23 September 1952, he had painted an earthenware plate with a restrained black and yellow abstract and quasi-calligraphic decoration, which he dedicated to his friends the Lacouturières9 in a once-off and relatively anecdotal episode. The creation of the Sèvres Vase on the other hand, enabled the artist to experiment with a design that was no longer intended as a decoration but instead as an objet d’art, constituting a veritable transposition of his pictorial research to ceramic art.

A Contenair of light

Using elements specific to ceramic techniques, including turning and enamelling, with this vase Soulages continued his exploration of the relationship between black and light that underlies all his work. The graphically linear ridges obtained by means of the tournasage technique on the surface of the vase, recall, as Mathieu Séguéla points out, the texture of the embossed or “formed” paper, produced by the painter in 1990. These ridges form the reliefs in which shadow and light come to play on the enamelled material, similar to the effect produced in his “outrenoir” paintings, worked by brushes and scrapers. (fig. 3).

Furthermore, by emphasizing the circular shape of the vase, these ridges offer Pierre Soulages the unique opportunity to sculpt the light not just in two, but in three dimensions. The application of black and grey enamel with a brush, on the other hand, may be said to echo the artist’s painting practice. We can see the same type of vibrations and modulations of the black paint, according to the thickness and saturation of the brush, in works like Peinture 130 x 162 cm, 21 juillet 1958 (fig. 4), but also the reliefs formed deep in the matter of an “outrenoir” such as Peinture 200 x 255 cm, 18 octobre 1984 (fig. 5).

From 1979 onwards, black paint completely invaded the surface of Soulages’ canvases, bringing about, through the play of reflected light caused by the differences in textures of the pictorial material, a kind of negation of the black itself, or to quote the artist’s own words: a “beyond black, a light transmuted by black.”10

Here however, the light is not only shaped by the exterior decoration of the vase, it is also, and above all, shaped by the interior, covered with a layer of 400 grams of fine 24-carat gold, revealed by the two openings, one vertical and the other lateral. The half-disc of the lid allows the light to enter while the side disc enables its reflection, according to the self-proclaimed intention of the artist: “A vase, usually, is empty and dark. I wanted mine to contain the light.”11 While porcelain traditionally lends itself more to a play of light based on the transparency caused by the vitrification of kaolin, here the opacity, relief and addition of an external material base the relationship of this vase to the light, of which Soulages readily underlines the “emotional and symbolic charge”,12 of an ontological order, at the cornerstone of his work.

“A vase, usually, is empty and dark. I wanted mine to contain the light.”

While it maintains a very strong conceptual link with all of Soulages’ pictorial production, the Sèvres Vase may be said to resonate in direct ways with many of his paintings from the 1950s, where the light seems to emerge from the depths of the canvas. The large rectangular vertical and horizontal strokes superimposed on such canvases form various games of contrasts and transparency, hollowing out the effects of depth by means of “luminous gaps”.13 This is the case with several pieces within the FGA Collection. For example, Peinture 81 x 60 cm, 28 novembre 1955 (fig. 6), and even more so, Peinture 195 x 130 cm, 11 juillet 1953 (fig. 7), whose luminous quadrangular form piercing the dark-coloured sections bears the same bronze hue as the gold disc cut into the wall of the vase, a singularly strong echo that motivated the inclusion of exemplar no. 6/10 in the Foundation’s collections.

A tribute to Japan

This vase contains a dual reference to the 1950s: firstly, through the form, borrowed from Sèvres and modernized by Soulages, and secondly, through the subtle link with the artist’s early period, during which he discovered Japan, and the Japanese public in turn, discovered his artwork. Although Pierre Soulages travelled to Japan for the first time in 1958, his work had been exhibited there regularly since 1951 at each International Art Exhibition, and from that early date, he had forged friendly ties with many Japanese artists and intellectuals.14 The fact that Soulages was chosen to produce this sumo trophy, a decision made in consultation with Maurice Gourdault-Montagne, then-French ambassador to Japan, and Thierry Dana, diplomatic adviser at the Élysée, makes perfect sense in such a context.

Soulages himself has always denied the influence of Japanese art, and in particular calligraphy; his pictorial practice does not refer to any external reality and is not based in any way on gesture, unlike the work of Hans Hartung or Georges Mathieu, although it contains many “fortuitous similarities”, justly noted by Mathieu Séguéla. The approach adopted for the creation of this particular vase however, constitutes an explicit celebration of the art of the Land of the Rising Sun.

Indeed, the material itself—porcelain—brings to mind an ancestral tradition or art in Japan, although undoubtedly less so in the Western imagination, that of raku. Moreover, the disc cut in the side wall evokes, almost literally, the red disc, symbolizing the rising sun of the Japanese flag, and, through it, the legend of the Shinto goddess Amaterasu coming out of her cave. It is also possible to see references to dohyō, the sacred circle of sumo, a ring that cannot be overstepped by its wrestlers. Finally, in a more personal interpretation, this disc can be read as a subtle allusion to the Latin root of the artist’s own name: “sol agens”, meaning “powerful sun”, a primordial part of all his work.

Created after fifty years of activity, the vase produced in Sèvres in 2000 summarizes and, if one could say, “contains” all of Soulages’ work, combining and condensing the experimentation simultaneously carried out on the relationship between black and light, and on the transposition of such research into media other than painting.

It is also, in itself, a masterpiece of contemporary ceramics, recognized as such: it received the prize for the most beautiful object at the Pavilion of Arts and Design in 2009 in Paris after the edition of ten copies of the vase. It also holds a significant place in various official institutions (Palais de l’Élysée, the French Embassy in Tokyo) and public collections (Cité de la Céramique, Sèvres, and the Musée Soulages, Rodez).

Fabienne Fravalo

Curator Decorative Arts Collection

Geneva, December 2021

This note is a revised and expanded version of the text written for the catalogue accompanying the exhibition In Praise of Light. Pierre Soulages / Takanabe Chikuunsai IV, held at the Fondation Baur, Geneva, from 17 November 2021 to 27 March 2022.

Notes and references

- Two other copies were created at the same time: one for the Palais de l’Élysée, and the other for Pierre Soulages as an artist’s copy or proof.

- (Slip) casting is a porcelain forming technique, which involves pouring the liquid paste into a porous mould: the water is absorbed by capillary action and the paste sticks to the walls of the mould as it dries. It is used to produce pieces that are thin and/or of large dimensions.

- The tournasage or tournassage technique is a secondary shaping technique that transforms the work in progress into its definitive form. It is performed directly on the raw, dry paste and consists of thinning and smoothing the walls on a whirling lathe, removing material.

- Suire, “Marie-Aimée, Soulages et Sèvres célèbrent le soleil levant” in Sèvres, Revue de la Société des Amis du musée national de Céramique, no. 27, 2018, p. 144-153.

- Cf. Moinet, Éric, “Peindre et modeler. L’expérience de la manufacture de Sèvres” in Le Bihan, Olivier (ed.), Céramique d’artiste: Derain, Dufy, Matisse, Miró, Picasso, Milan, Silvana, 2012, p. 141-149.

- Salvador, Léa, “Pierre Soulages et la manufacture de la Savonnerie”, [online:] https://fresques.ina.fr/soulages/fiche-media/Soulag00017/pierre-soulages-et-la-manufacture-de-la-savonnerie.html, consulted on 5 November 2021.

- Chamotte clay is a fine earth to which crushed terracotta is added. The latter facilitates drying and increases the resistance of pieces by limiting shrinkage.

- As the building has since been destroyed, Soulages’ work joined the Butler Institute of American Art, in Youngstown, Ohio in 2010.

- The decoration has since been covered by a glaze. Cf. Le Bihan (ed.), Céramique d’artiste: Derain, Dufy, Matisse, Miró, cat. no. 260, p. 252.

- Soulages, Pierre, “Du noir à l’outrenoir” (Preface to Dictionnaire des mots et expressions de couleur: le noir by Annie Mollard-Desfour, Paris, Éditions du Centre national de la Recherche Scientifique, 2005), in Pierre Soulages, Écrits et propos (texts collected by Jean-Michel Le Lannou), Paris, Hermann, 2009, p. 59.

- Soulages, Pierre, 2017, cited in “D’encre et de pierre, le Japon de Soulages”, [online], available on: http://www.pierre-soulages.com/dencre-et-de-pierre-le-japon-de-soulages/ (consulted on 29 March 2021).

- Soulages, Pierre, in Dillmann, Isabelle, “Entretien avec Pierre Soulages, ‘Le bâtisseur de lumière’ - Première partie”, Revue des Deux Mondes, 4 December 2019, [online], available on: https://www.revuedesdeuxmondes.fr/entretien-avec-pierre-soulages-le-batisseur-de-lumiere-premiere-partie/, consulted on 14 November 2021.

- Drugeon, Fanny, in Chassey, Éric de & Notter, Éveline (ed.), Les Sujets de l’abstraction. Peinture non-figurative de la seconde école de Paris. 101 Chefs-d’œuvre de la Fondation Gandur pour l’Art, exhibition catalogue [Geneva, Musée Rath, 6 May – 15 August 2011; Montpellier, Musée Fabre, 7 December 2011 – 24 March 2012], Milan, 5 Continents Editions, 2011, p. 136.

- Cf. Séguéla, Matthieu and Saint-Chéron, Michaël de, Soulages. D’une rive à l’autre, Arles, Actes Sud, 2019 and Gatel, Raphaël & Lutanie, Manon (ed.), Soulages in Japan, Dijon, Les presses du réel, 2017.

Bibliography

CHASSEY, Éric de, and NOTTER, Éveline (ed.), Les Sujets de l’abstraction. Peinture non-figurative de la seconde école de Paris. 101 Chefs-d’œuvre de la Fondation Gandur pour l’Art, exhibition catalogue [Geneva, Musée Rath, 6 May – 15 August 2011; Montpellier, Musée Fabre, ], Milan, 5 Continents Editions, 2011

FAŸ-HALLÉ, Antoinette (ed.), ROCCHISANI, Chantal and TROUVET, Catherine (ed.), Les vases de Sèvres: XVIIIe-XXIe siècles, éloge de la virtuosité, Dijon, Faton, 2014, another copy cited p. 274, colour reproduction p. 267.

FRAVALO, Fabienne, “Contenir la lumière. Soulages, Sèvres et le Japon…”, in Laure Schwartz-Arenales (ed.), Éloge de la lumière. Pierre Soulages / Chikuunsai IV (exposition catalogue, Geneva, Fondation Baur, 17 November 2021 – 27 March 2022), Milan, 5 Continents Editions, 2021, p. 25-31, cover reproduction p. 27-28; 57, cat. no. 6.

GATEL, Raphaël and LUTANIE, Manon (ed.), Soulages in Japan, Dijon, Les presses du réel, 2017.

Le BIHAN, Olivier (ed.), Céramique d’artiste: Derain, Dufy, Matisse, Miró, Picasso, Milan, Silvana, 2012, another copy cited p. 298, colour reproduction p. 143

SÉGUÉLA, Matthieu and SAINT-CHÉRON, Michaël de, Soulages. D’une rive à l’autre, Arles, Actes Sud, 2019, another copy cited p. 70-72, colour reproduction p. 71

SOULAGES, Pierre, in DILLMANN, Isabelle, “Entretien avec Pierre Soulages, ‘Le bâtisseur de lumière’ - Première partie”, Revue des Deux Mondes, 4 December 2019, [online], available on: https://www.revuedesdeuxmondes.fr/entretien-avec-pierre-soulages-le-batisseur-de-lumiere-premiere-partie/, consulted on 29 March 2021

SUIRE, Marie-Aimée, “Soulages et Sèvres célèbrent le soleil levant” in Sèvres, Revue de la Société des amis du musée national de Céramique, no. 27, 2018, p. 144-153